Case Study: Recalcitrant Plantar Warts

Introduction

I give primacy of place to emergency medicine as my area of expertise. However, this past year, with the undertaking of the Cardiff Practical Diploma in Dermatology as my inspiration, I am now also an Associate at a dermatology office in Canada. I assess and treat patients with dermatological conditions independently in this setting, but I also have access to a dermatologist if required.

One of the most common presentations seen during my dermatology clinics is cutaneous warts. However, because this is not a clinically emergent condition many of these patients feel embarrassed to request multiple visits regarding the same issue with their family physician. Once they are referred to us, they often open up about their wish to be more aggressive about the treatment of the warts.

It was during one of these consultations that I met a 57 y/o woman whom I will refer to as Ms. P. Ms P was very forthcoming and co-operative about her troublesome recalcitrant plantar warts on her foot. Her story defined for me how a “simple dermatological problem” could follow a patient through the course of their life. Furthermore, she was pleased that I wanted to use her condition as a case study from which to share the principles of plantar wart therapy, and their effect on a patients lifestyle. While a comprehensive review of all the numerous cutaneous wart therapy options is not possible in this one case study, I will attempt to describe in details those most relevant to Ms P care and treatment.

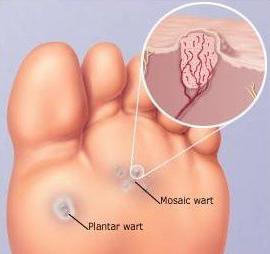

Warts in general are benign epithelial proliferations of skin and mucosa caused by infection with the human pappilloma virus (HPV) (1,2,3). Cutaneous warts are the most common skin lesions caused by the HPV virus. More then 100 different HPV types have been identified thus far (1,2,3). The most common infection is HPV 2 on the feet and hands.(3) No single therapy is known to cure all warts. Many warts will require a combination of treatment methods. Treatment is aimed at relieving the patients physical and psychological discomfort and preventing the spread of the warts via auto-inoculation (1). Some different clinical types of warts include: common warts (verruca vulgaris), filliform warts, flat warts (verruca plana), and plantar warts (1). While genital warts are important as well, they are caused by HPV 6 and 11 mainly, they have separate considerations under verrucous oral and genital lesions that will not be addressed in this case study (3). Most cutaneous warts are asymptomatic, but those occurring in the palmoplantar area can be tender. My case will be discussing the recalcitrant plantar wart which is frequently found coalesced into a cluster of one large wart surrounded by many smaller warts (1). While a plantar wart can be single or multiple; when it appears in the manner of our case study it is also known as a ‘mosaic wart’ or ‘myrmecia’ (1, 2). Because the plantar wart can be found beneath pressure points, such as the heel in the case of Ms P., they can also be the cause of a lot of discomfort.

The differential diagnoses of warts can include: callous/corn, angiokeratoma or melanoma. (1,4,5). It is important to differentiate an HPV infection from the above conditions, as missing a melanoma can have dire consequences. While plantar melanoma’s account for only one third of lower leg melanoma’s, they make up two thirds of misdiagnosed melanoma’s of the foot (4). If one suspects the lesion could be a melanoma, either a biopsy for confirmation of diagnoses, or complete excision with pathology would be appropriate, depending on your level of comfort. Urgent referral to a specialist would be expected.

Callouses and corns are thick hard skin deposits that cause pain and can sometimes be difficult to differentiate from cutaneous warts. The observation of small black dots (thrombosed capillaries) or bleeding points after debridement of the overlying skin can help differentiate a cutaneous wart (with underlying vessels) from a corn or callous (no underlying blood vessels). Angiokeratoma’s can mimic cutaneous warts, but are composed of a benign proliferation of local capillary blood vessels (5). They often have a bluish/red color and may also have a scaly surface (5).

Case Presentation

Ms P presented with a prolonged 20 year history of having plantar warts on her left foot. Her last treatment was over 5 years ago, at which time she stated she had “given up” and thought she would have “her little friend forever”. She recently noticed two new satellite lesions, and had shown her family physician in hopes of trying any new therapy that had been discovered to prevent spreading of the warts. She was amenable to being referred to a dermatology office, and was thus referred to my clinic with a request for laser therapy for her warts. This request was based on the fact that she had had multiple treatment modalities in the past for this wart including: salicylic acid treatment, cryotherapy , and diphenylcyclopropenone (DPC) immune treatment without success. Ms. P did not remember the details of the therapies utilized in the past but said she likely had some improvement and stopped treatment prior to complete resolution of the warts, and regrets that fact. She stated that she remembers she did try the SA daily but not for longer then a few weeks, and had “occasional” cryotherapy sessions separated by many months. She described the DPC wart treatments as ineffective despite numerous in clinic sessions. It was explained to Ms. P that Laser therapy for warts is typically reserved for treatment resistant warts after an initial reduction in hyperkeratosis is achieved, due to the physical depth of penetration of the laser.

She was an otherwise immunocompetant patient with mild chronic venous insufficiency of the legs, grade I. On physical examination, she had warts on her left heel. She denied any warts or lesions elsewhere on her body. There was a mosaic plantar wart, with satellite growths (picture 1) on her left heel.

Basic Foot Care and Wart Therapy Education

We explained to her that warts were from a virus and could spread, and she was at risk for auto-inoculation if she pared or scrubbed her feet vigorously (1,2). She admitted that she had not understood this concept before. She shared that she had recently in the past few months been pumicing her foot in the shower. She was educated not to be barefoot in public places, and to not pick/shave or pumice her foot to prevent the spread of the wart. She was asked to keep her feet dry and clean, while changing her socks daily. She was asked to wear comfortable shoes, without pressure points. She understood that although many warts usually go away on there own, certain types (like her plantar mosaic wart) are resistant to treatment and therefore can not always be cured. They often also require a significant time commitment to therapy by the patient (1,2). The treatment of plantar warts can be painful, and sometimes can leave a scar, which on the sole can be even more uncomfortable. I explained to her that we would begin again with the basics of wart therapy to bring the wart to a more superficial level, which would then make it more amenable to laser therapy if required. She was grateful for the time spent in educating and counseling her regarding basic wart therapy, as she stated she had not understood completely before her condition.

With all this information, she agreed to begin therapy again as she was highly motivated. She confided that she did not feel comfortable going to public swimming pools because of her condition, and that she was in a new social relationship which motivated her to treat her plantar warts. This new information helped me understand her new found determination to pursue her wart treatment. At this point, I spent some extra time explaining to Ms P, that a plantar mosaic wart was the most difficult type of cutaneous wart to treat, and that there may not be a favorable end point despite our best efforts given her prolonged history (3,6). In one study salicylic acid, cryotherapy and a wait and see approach after 13 weeks had no clinically relevant difference in effectiveness (8). Despite this cautionary tale, Ms P requested me as her ally in one final attempt to cure her wart, as the wait and see approach had definitely failed.

She had two aggressive freeze thaw cycles (FTC) of 15 seconds via cryotherapy in clinic by myself on her first visit. She was given a topical prescription (30% salicylic acid in petrolatum) and advised to paint on the wart nightly under occlusion overnight for two weeks, then two weeks off (no salicylic acid) , then repeat the cycle up to a total of three times. I asked her to apply the treatment after she had soaked her foot in warm water for up to ten minutes to allow better penetration of the topical therapy. I also further explained to her that the two weeks off (no salicylic acid time period) was important as it allowed time for the chemical exfoliation to occur, and not to skip this aspect of the regiment. During this time she was advised that duct tape occlusion therapy could be used at home if she wanted (6). She was highly determined, and so we explained that every 24 hours she should change the sticky grey duct tape and keep the warts otherwise occluded during the time she was not using salicylic acid. It was my hope that the combination of the different therapies would allow the wart to become more superficial and amenable to laser therapy at her visit in 3 months. The Cochrane Collaboration review (2012) Topical Treatments of Cutaneous Warts comments that salicylic acid used in combination with cryotherapy may work better than salicylic acid alone (3). She was also counseled that she could have another cryotherapy session in 4 weeks time. Ms P was made aware that she could book a sooner consultation if she felt she had any concerning side effects of blistering and irritation, or if she felt there was no improvement in 2 months time. After discussing the case with the dermatologist, he agreed with this plan. I felt it was important to confer with my colleague who would possibly be administrating the laser therapy once the plantar wart was amenable.

Wart Therapy Principles

The principles of first line therapy of plantar warts consists of a) counseling the patient b) pressure off loading c) occlusion therapy (e.g.. duct tape) d) destructive methods through chemical peels or cryotherapy or a combination of both.

Pressure Off-Loading

Counseling requires the patient be educated regarding the condition and the potential for treatment failure despite time consuming and slightly painful treatments.

Pressure off loading consists of a ring cushion cut to the shape of the plantar wart used under the foot during weight bearing moments (in shoes, socks). Mrs. P was advised on her first visit to create a ring cushion from a sponge, cut in the shape of her mosaic wart, and tape to her foot (this allowed her discomfort to be relieved via pressure off-loading while therapy occurred). Of note in this case, with the discussion of pressure off-loading, Mrs. P confided that she had compression stockings which she now realized were making the plantar warts more unbearable.

On her second visit, after 4 weeks (no picture) for a repeat cryotherapy session (I again repeated two 15 second FTC cryotherapy), Mrs P stated the addition of the ring cushion for beneath her foot relieved her discomfort while still allowing her to maintain her pressure stocking regiment. She was very happy with the results to date with the therapy, and although time consuming she felt it was “worth it” because she could see the warts shrinking. I reminded her that we were aiming for a complete and sustained clearance for her warts this time around. She remained optimistic. On exam, at the second visit, her satellite lesions had disappeared and the main plantar wart had decreased in size subjectively.

Occlusion Therapy

Occlusion therapy, also referred to as duct tape therapy stuck onto warts, has been observed in a number of trials. Its mechanism is not well understood (3). Focht et al. in 2002 first brought attention to this therapy by utilizing silver duct tape on warts and compared it to cryotherapy (6). Eighty five percent of the patients using duct-tape on their warts after two months had complete resolution of their warts. In comparison only 60% of the children receiving cryotherapy had resolution of their warts after two months. Newer trials have looked at silver duct tape vs clear duct tape, the former appears to have better efficacy (3). Authors (Focht et al. 2002) also concluded that if a wart was responding by the three week mark, then outcome was positive; but if the warts were not responding by the three week mark, then duct tape was not likely to be of any benefit. In this study the duct tape was left on for 6 days (re-applied only if it fell off); then a 12hour over-night break after soaking the wart for 10 minutes and pumicing any extra loose epidermis, and then restarting the regiment for a total of two months (6). In retrospect I might have tailored my advice regarding the use of duct tape to include the 12 hour break and stop if no improvement in 3 weeks. However, I still would not recommend the paring/pumicing of the wart as I feel the risk of auto-inoculation is too great from this method. I feel the process of removing and reapplying the tape helps in de-bulking the wart without this risk.

Topical Therapy

Salicylic acid (SA) is painted onto warts and one of the most effective, safe and studied treatments for wart therapy to date (1,2,3). I use 30-40% SA concentration depending on the wart and site, reserving the higher concentration for adults and plantar warts. I began therapy with a 30% SA treatment in Ms P, as I was being cautious secondary to the combination of therapies I was utilizing, but in retrospect, a higher concentration would have likely been fine. Salicylic acid products may contain a caustic agent (causes superficial cell death by chemical dehydration of the tissue) such as monochloroacetic and trichloacetic acid (80-90% solutions) or a viricidal agent such as glutaraldehyde. Adverse effects can include: dryness, fissuring and contact sensitivity. I normally use SA without any of these extra components, as I find good efficacy with SA if used under occlusion. Also, I have been advised by senior colleagues that the tolerability is considerably improved by patients in this manner. Most topical treatments are thought to work to clear warts through two mechanisms: 1) the cells with HPV completely destroyed by the method are eradicated and 2) partially damaged infected cells are said to stimulate a natural immune mediated mechanism of eradication.

Silver nitrate, a topical chemical cautery, is another option recommended in the literature for first line therapy that can be used twice weekly (1). Patients do not find this option very convenient, finding a parking spot and coming into the office numerous times in a week is not preferential, and so we do not offer this option in my clinic.

Cryotherapy

Recalcitrant plantar warts require aggressive cyrotherapy FTCs (which may be used as first line therapy or second line therapy). This refers to any therapy that induces cold damage which 1) damages the HPV infected cells vascular supply and 2) stimulates the immune system to eradicated the warts (3). My use of 2 cycles of 15 second FTC’s was not as aggressive as I first thought, but I would still begin with this type of session. Although, if shown to be tolerated by the patient (which it was on her second visit) I would have then suggested two 30 second sessions the second time. If these treatment methods fail, other modalities must be considered.

Systemic Zinc Replacement

Second line therapies include a wide range of options in the immunotherapy category.

Patients with zinc deficiency were shown to have a predisposition to viral warts in the patients studied (9). Zinc is a micronutrient necessary for the function of normal cells. As such, oral zinc sulphate (10mg/kg at a max of 600mg/day) is an effective, inexpensive and painless way to treat warts (9). The lack of any serious complications from oral zinc sulphate replacement makes it a good option to consider in recalcitrant wart therapy. On Ms. P’s follow up therapy at three months I plan to suggest a zinc serum level and replace if a deficiency is noted.

Diphenylcyclopropenone Immunotherapy

Diphenylcyclopropenone (DPC) and squaric acid dibutylester act to induce a type IV hypersensitivity reaction against the contact agent bound to human or viral proteins to stimulate clearance of the wart (1,3). They are typically applied as solutions to the warts to induce an immune response once the patient has been sensitized. I do not use this method in my office due to the risk it poses to the person administrating the therapy (therapist sensitization), but it remains a viable option for recalcitrant warts. As Ms. P had already tried this method unsuccessfully, and there are no randomized controlled trials to date to support this therapy I chose not to re-administer this therapy.

LASER

Finally, Laser therapy is gaining new ground. Laser’s are designed to essentially destroy the infected tissue, and cause an autoimmune reaction at the site of the therapy to induce wart clearance (7). Unfortunately there are no randomized controlled studies looking at laser for wart clearance therapy (3). A retrospective case note review and questionnaire-based survey of 22 patients treated with carbon dioxide laser using an excision technique with recalcitrant warts, achieved a 95.5% success rate (7). The procedure was well tolerated by the patients and remains an option for Ms. P as we have a laser specialist at our dermatology clinic. Despite the small number of patients within the published study, this is a promising new avenue for wart therapy research.

The greatest breakthrough in the treatment of HPV in general has been the HPV vaccine, tested against cervical cancers and anogenital warts. Anecdotal evidence is showing a much broader effect, possibly through a cross-protective effect. A case report of 31 y/o male with 30 refractory cutaneous warts which cleared after administration of the qudrivalent HPV vaccine demonstrates the potential of an exciting new role for this vaccine (10).

Learning Points

There were two main learning points in this case study for me. First, after reviewing the literature and the 2012 Cochrane Collaboration it became clear to me that there was no one cutaneous wart therapy that would be 100% successful. Treatment had to be individually tailored based on the patient’s motivation, circumstance and wart specificities. Ms. P was a highly motivated and determined patient at the time of our first encounter. I am confident that a lot of her success came from her mental determination and commitment to the therapies. This case further highlighted to me the importance of transparency with a patient with regards to treatment success. Although I was hesitant to share the evidence which suggested that their would be poor outcome for her plantar wart therapy because I thought Ms. P might lose hope. In actuality this information only served to increase Ms. P’s fortitude in clearing her warts. As well, even if this was not the case, it is important for the patient to have realistic expectations with regards to any therapy. Furthermore, the importance of how a therapy is administered seems to be even more important than the actual therapy itself. In the case of Ms. P we repeated several therapies she had used in the past with greater results the second time around, likely due to her increased compliance to the regiment.

My second learning point arises from the treatment choices I utilized. In the future I plan to use a tape measure to assess the size of warts in clinic on first encounter. An objective measure of wart shrinkage would be more useful than a subjective assessment. As mentioned previously I would also consider her zinc serum level status and any underlying factors that may contribute to her viral load. I would have increasing the the aggressive cryotherapy FTC’s on the second visit secondary to her tolerance. This is supported by the Cochrane Collaboration Review (2012) which suggests that more aggressive cryotherapy is more effective (3). I was pleased with the how much pressure off loading had improved Ms. P’s discomfort from her plantar warts. Ironically, despite the fact that the plantar wart was on a non obvious setting (the bottom of the foot), it still caused significant social discomfort. In light of this, I think it would be important, in the future, to assess the effect of quality of life on my patients with warts more formally. This would help me to suggest more aggressive therapies for those who seem more severely afflicted by there condition.

In conclusion, this case study demonstrates the importance of patient compliance and committment to therapy for a successful outcome. It is my role, as a physician, to provide the patient with the educational foundation and tools necessary for the patient to be successful in their quest for a cure for cutaneous warts. My literature review of treatment for cutaneous warts has enabled me to have an open mind when I see my next patient with warts. I will spend the time to find out how the wart effects their quality of life and how motivated they are to find a cure.

The greatest breakthrough in the treatment of HPV in general has been the HPV vaccine, tested against cervical cancers and anogenital warts. Anecdotal evidence is showing a much broader effect, possibly through a cross-protective effect. A case report of 31 y/o male with 30 refractory cutaneous warts which cleared after administration of the qudrivalent HPV vaccine demonstrates the potential of an exciting new role for this vaccine (10).

References

- Dall’Oglio F, D’Amico V, Nasca M et.al. Treatment of Cutaneous Warts: An Evidence-Based Review. Am J Clinic Dermatol. 2012;13(2):73-96.

- Boull C and Groth D. Update: Treatment of Cutaneous Viral Warts in Children. Pediatric Dermatology 2011;28(3):217-229.

- Kwok C, Gibbs S, Bennett C et al. Topical Treatments of Cutaneous Warts (Review). The Cochrane Collaboration. 2012; 9:1-179

- Schade V, Roukis T, Homann J et al. “The Malignant Wart”: A Review of Primary Nodular Melanoma of the Foot and Report of Two Cases. The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery 2010; 49:263-273.

- Dunnihoo M, Kitterman R, and Tran D. Angiokeratoma Presenting as Plantar Verruca: A Case Study. Journal of Am Podiatric Medical Assoc. 2010; Nov-Dec 100(6):502-504

- Focht D, Spicer C, Fairchok M. The Efficacy of Duct Tape vs Cryotherapy in the Treatment of Verruca Vulgaris (the Common Wart). Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002; Oct 156;971974.

- Oni G and Mahaffey P. Treatment of Recalcitrant Warts with the Carbon Dioxide Laser Using An Excision Technique. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy 2011;13:231-236.

- Bruggink S, Gusselkloo J, Berger M et al. Cryotherapy with Liquid Nitrogen versus Topical Salicylic Acid Application for Cutaneous Warts in Primary Care: Randomized Controlled Trial. CMAJ. 2010;182(15):1624-1630.

- Al-Gurairi F, Al-Waiz M, Sharquie K. Oral Zinc Sulphate in the Treatment of Recalcitrant Viral Warts: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Br J Dermatol. 2002; Mar 146(3)423-431.

- Venugopal S, Murrell D. Recalcitrant Cutaneous Warts Treated with Recombinant Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine (Types 6, 11, 16, and 18) in a Developmentally Delayed, 31-Year-Old White Man. Arch Dermatol. 2010; May 146(5)475-477.